PALIMPSETS IN PONTE CITY

Palimpsests in Ponte City

Chapter 3

Though Ponte’s longtime claim to fame was being the tallest residential tower in Africa, tenants complained that the lifts would often break down and stop working.

Their frequent malfunction became a reminder of the continued lack of investment in technologies that best serve Ponte’s residential community. The perpetual state of disrepair rendered vertical mobility a spatial uncertainty. Staircases became an important alternative, an architectural feature that represents both duality and contradiction. Though stairs can be passages to better health, fitness and longer lifespans for the able-bodied, they also become a stigmatised barrier for those who do not have the luxury of time or physical capacity to reap the same rewards.

Walking through Ponte’s staircases also reveals these passageways as social spaces of various kinds. On the steps, residents sometimes sit casually talking, kids are playing there or others are handwriting messages on the concrete walls. Almost like a public message board, management sometimes post notices for residents to read on the wall that faces the staircases.

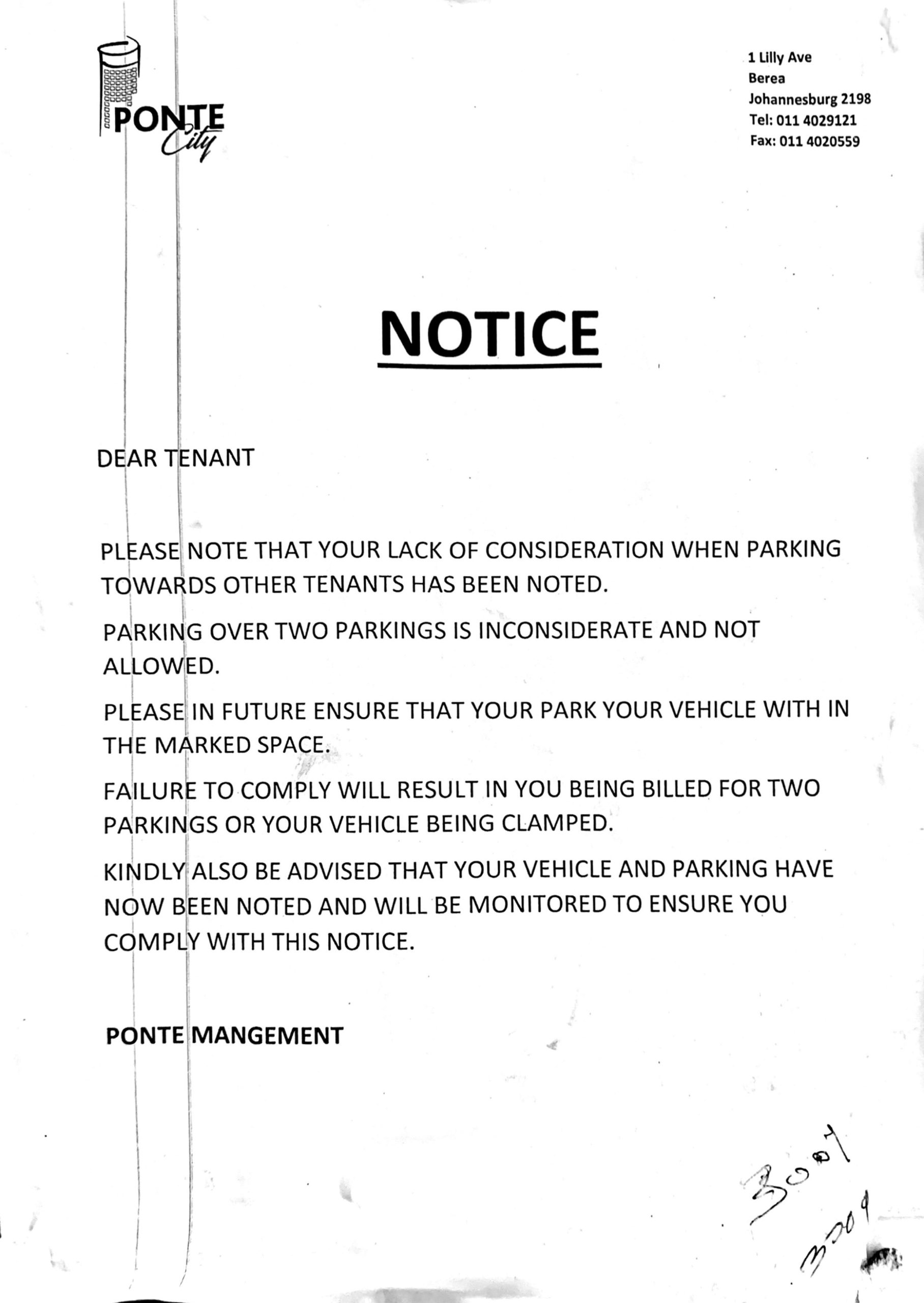

This notice was posted on 16 May 2018 and signed by Ponte management. Their request reads of immediate disapproval, where tenants are addressed as those who have shown other tenants ‘a lack of consideration when parking’. Residents are warned that parking over two spots is inconsiderate and strictly prohibited.

It is not until the conclusion of the notice that tenants are informed that they have already been recorded and monitored, and if they violate these rules, vigilant surveillance will continue to ensure that the rules are followed. The notice may seem innocuous, yet the management letterhead, the all-caps font and the tone all operate to cast Ponte as a social space that requires order, obedience and discipline, to be meted out by Ponte’s managers.

Photocopies of the notice on each floor do not go undamaged. Some residents may have read the notice, but then chose to rip it off the wall in retaliation.

Though easy to dismiss, lifts are important in that they offer residents a vertical passage for mobility between their home and city surroundings.

No one would have found a tall skyscraper above five floors a desirable place to live had it not been for the invention of the passenger lift. Ponte has eight. These can only be accessed by passing through the fingerprint-enabled gates stationed near the security guard station at the lobby promenade above the seventh parking level. Lifts are the architectural domain in which highly complex social relations occur. What is apparently a simple transport device ended up redefining the spatial organisation of residential living in cities worldwide. David Harvey’s concept of time-space compression is apt given how the lifts’ directional change compressed time and distance going skyward. Rather than think about how public transport compresses the temporal distance between geographically separate points on a horizontal plane, one must consider how the lift compresses the temporal distance between geographic points in the vertical.

When lifts work efficiently, they become symbols of a society’s advanced modes of production. In theory, they promote speed, efficiency and convenience. But when lifts fail, falter or move too slowly, one becomes impatient and complains of the brokenness found in what is expected to be a system conducive to optimal capitalist output. When infrastructures are in consistent disrepair, passengers become keenly aware of how even the most ubiquitous and mundane of technologies are hinged upon a state of precarity. Residents who use Ponte’s lifts on a daily basis can lose faith in the very system that not only made such technologies commonplace, but also convinced thousands of urban dwellers to make homes of Johannesburg’s tallest high-rise buildings.

Ingrid Martens’ documentary, Africa Shafted: Under One Roof, is a prime example of how the improvisational coping strategies for broken physical infrastructures actually reproduce other figurative states of brokenness reflected in the social environment. The lift forces strangers to meet and interact when they would not otherwise. In the process of filming, Martens discovered stories of xenophobic prejudice and attack. She began filming in Ponte in 2006, a year before investors David Selvan and Nour Addine Ayyoub were scheduled to buy and rehaul the building. The new owners evicted many of the same tenants featured in the documentary. At least two of the interviewees were killed in the xenophobic attacks of 2008.

In each shot of Africa Shafted are candid interviews with various passengers who converse with Martens for the duration of their ride. A montage of residents’ nationalities is offered—some are from Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo (Congo), Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Two of the passengers identify themselves as coming from South Africa, one from the township of Soweto and another from the old mining town of Welkom in the Orange Free State. Although only 10 African countries are named amongst the residents interviewed, the perception is that Ponte houses nearly every African nation. As one Ugandan resident states, ‘it is nice to meet different tribes here because I now know I can greet almost in one language in maybe 30 countries’ (sic). In one voiceover, a resident proudly exclaims that Ponte is like the Organisation of African Unity.