PALIMPSETS IN PONTE CITY

Palimpsests in Ponte City

Chapter 2

At midday, as the sun’s rays beam straight down into the building’s hollow interior, light is refracted by the curving hallway walls and windows of each floor.

The view from the middle of the core’s rocky foundation, looking straight up at the sky, is awe-inspiring. The light appears as a white pinhole—an aperture through which light travels. But the light that seeps into the stairwells and passageways of Ponte is but twilight. The austere darkness of the surrounding concrete absorbs what limited light remains after one descends deep into the abyss of Ponte’s negative space.

Though different sources claim there was anywhere between three and 14 storeys of litter, these heaps were created by residents who would chuck their rubbish out the broken hallway windows facing the interior core. The fascination with the rubbish as somehow “sinister” was imagined by the media as proof of Ponte’s declining character.

In 1995, the Ministry of Correctional Services invited American architect, Paul Silver, to survey derelict buildings in inner-city Johannesburg. Silver stated that Ponte was a ‘lousy apartment building, but a perfect prison’. Though Ponte never became a penitentiary, the building was designed for the violent erasure and surveillance of several racialised populations. This act of waste disposal in Ponte’s core could arguably be interpreted as a small but radical act of defiance. Black residents reclaimed that space by refusing an oppressive white gaze and creating a blockade of rubbish.

Ponte has gone through various stages of reconstruction, remodelling and reinvention since 2000. In anticipation of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, the Johannesburg Development Agency approved the investment of R900 million in rebuilding and developing the city. Two property developers, David Selvan and Nour Addine Ayyoub of Investagain, purchased Ponte and promised to invest R200 million. Redubbed “New Ponte”, Selvan and Ayyoub had grandiose dreams of constructing upmarket units, including six penthouses, each three floors and 265 square metres of space. They would revive ideas developed by Ponte’s original architects in 1975, but give it a more contemporary upgrade by including a fine dining restaurant, grocery store and a Virgin Active gym. The listing prices were to open at R340,000 for a bachelor pad and up to R900,000 for a three-bedroom flat.

But the economic recession of 2008 liquidated Investagain and forced Selvan and Ayyoub to abandon the New Ponte project altogether. By 2009, the Kempston Group bought Ponte back and evicted unwanted tenants, cleared out the rubbish in the hollow core and hired landlords to manage the building with renewed military fervour. Making Ponte a “safe” space to live came at the price of turning it into a panopticon. The building had surveillance cameras installed throughout, strict fingerprint security and registration of overnight guests. Flats occupied by immigrants were also subject to surprise inspections, and these residents had to provide proof of a valid visa at any time

Ponte’s core inspires a response akin to what philosopher Edmund Burke describes in his theory of sublime art.

Burke defined ‘the sublime as an artistic effect productive of the strongest emotion the mind is capable of feeling’. He wrote, ‘whatever is in any sort terrible or is conversant about terrible objects or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime’. Distinct from the beautiful, Burke associated the sublime with that which was dark, gloomy and intense.

Ponte’s immense scale inspires all the emotions that Burke claimed made for great art, and Ponte’s most popular discursive markers indicate just how sublime its architectural form truly is. It has been selected as the filming location for such science-fiction films as Resident Evil: The Final Chapter, District 9, Chappie and Dredd. (Less dystopian, however, was the use of Ponte’s spiralling parking lot and hollow core for Beyoncé Knowles’ musical film, Black is King.) Even if Ponte’s community enjoys bouts of momentary lightness and joy in the mundane of everyday life, voyeurs still derive pleasure from the scandalous urban legends linked to Ponte. Unverified rumours shrouded in the language of death and illegality run rampant in news headlines and social media posts. For better or worse, the building remains fascinating precisely because it is an enigma.

The base of Ponte’s core resembles a geomorphic landform. Ponte’s original architects planned to use these 3,000 square metres of exposed earth as an indoor ski slope.

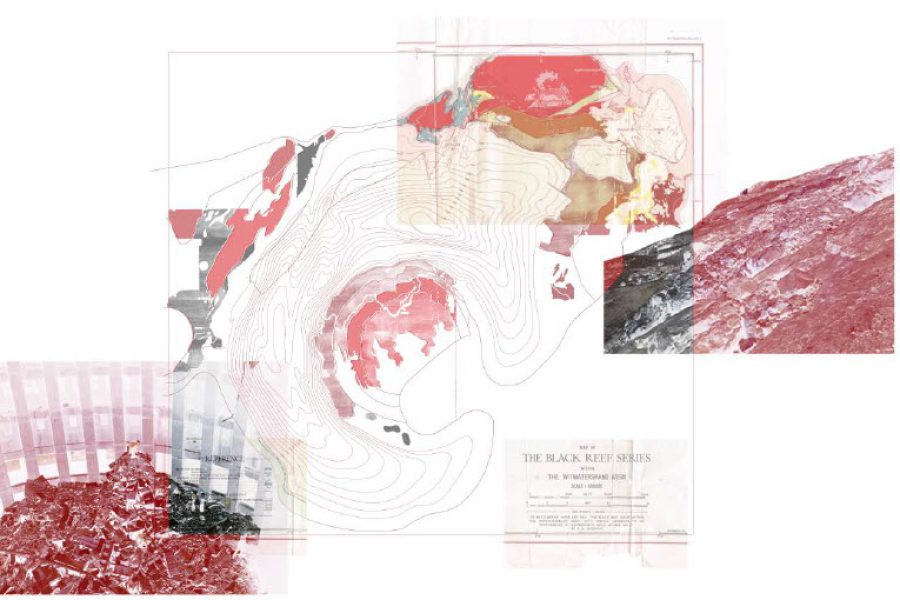

Investagain’s builders discovered the rocky base beneath the tower of litter and tried to blast the rocks into an even flat surface. When that failed, Selvan and Ayyoub planned to turn the core into a rock-climbing wall instead. None of these dreams ever came into fruition. A powerful geological agent, it is as if Ponte’s concrete base resists manipulation. Hidden beneath this “cement mountain” are layers of shale that covered the precious metal that earned Johannesburg its title as a “city of gold”.

Where Ponte would eventually be built, alluvial gold was found by white South African prospector Pieter Jacob Marais in 1853, and later by Australian prospector George Harrison on a farm called Langlaagte in 1886.

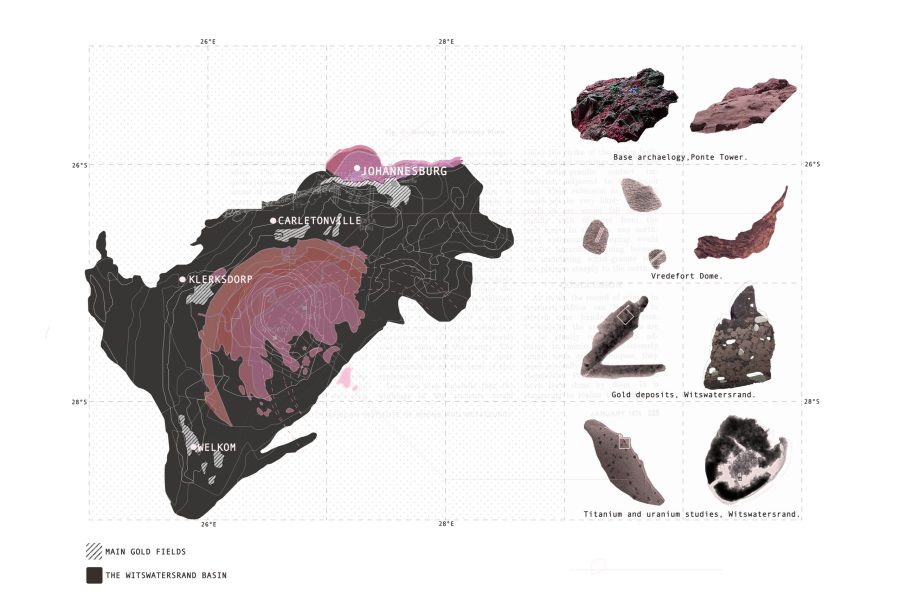

Click on the image to expand

Situated within what geologists call the Witwatersrand Basin, Johannesburg is also colloquially known as the Rand. The Afrikaans word Witwatersrand means “ridge of white waters”, a word imbued with its own mythological origins. A great number of Afrikaans words have been assigned to South Africa’s geomorphological features. For example, the Rand overlooks the rolling grasslands known affectionately in Afrikaans as the veld, or in English, “open country”. On the surface, the Witwatersrand and veld are words used to describe one’s appreciation for the land’s aesthetic qualities. But for South Africa’s Indigenous Khoi, San and Bantu-speaking populations, these words are a sore reminder of the disproportionate power that settler colonials had to name, claim and possess land that did not belong to them. For colonisers, foreign land is always “open” and theirs for the taking. What is violently buried are the stories of the land—and those who stewarded it—long before European colonial encounter.

Land was topographically reimagined and scarred by colonial and apartheid categories of race, ethnicity, gender and social class. What is referred to as “the environment” is not simply a neutral description of the Earth’s untouched topography, geology or ecology. On the contrary, the environment is a colonial construct whose social-material relations bespeak the unjust appropriation and exploitation of land and labour in the name of Western “progress”. Urbanism disrupted the slowness of geological formation in exchange for speed, efficiency and development. As cities developed their own social and cultural patterns, the physical structures that make up South African cities like Johannesburg have had unanticipated social and environmental consequences that far outlive their predecessors.

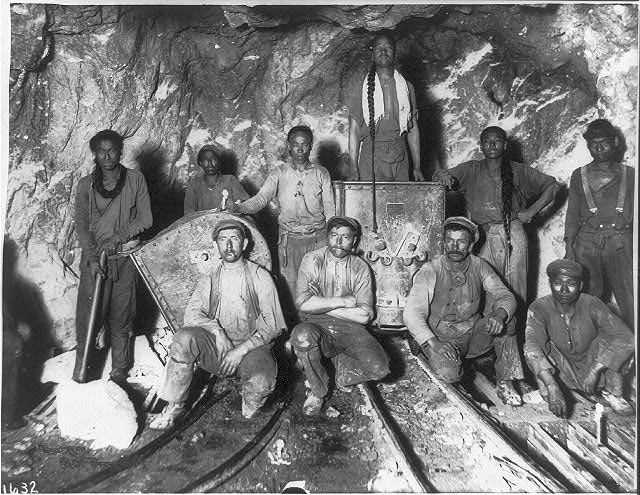

As Johannesburg quickly grew, colonial administrators sought more efficient ways to extract gold with cheaper labour. Black, Coloured, Indian and Chinese miners were all recruited to work for white bosses.

In the outcrop mines, miners were working at depths of 1.5 kilometres underground. Drilling was a dangerous and precarious task, and before commencing, dynamite was sometimes used in abandoned holes to break up rock to commence drilling. But the structural integrity of the ore was weaker in some sections than others. Being “caved in” whilst working was a constant threat. The life of a miner meant navigating multiple risky and deadly disasters.

Later urbanisation moved the mine shafts to the city’s periphery. Ponte sits on the topmost geological layers that conceal these troubling histories of the land and its people. Residents living in the township of Soweto still suffer bodily from the mine dumps left scattered and abandoned on the edges of the city. Many of the extracted minerals formerly existed in oxygen-free soils. Once the sulphur in these ores interact with oxygen on the surface, they have a detrimental impact. Much of the discarded tailings contain uranium, lead and arsenic. When the iron pyrite in gold-bearing ores oxidises with insoluble ferric oxide, the chemical reaction releases sulfuric acid that is carried away in oxygenated rainwater. These chemicals corrupt ground water and pose serious public health risks to nearby communities.

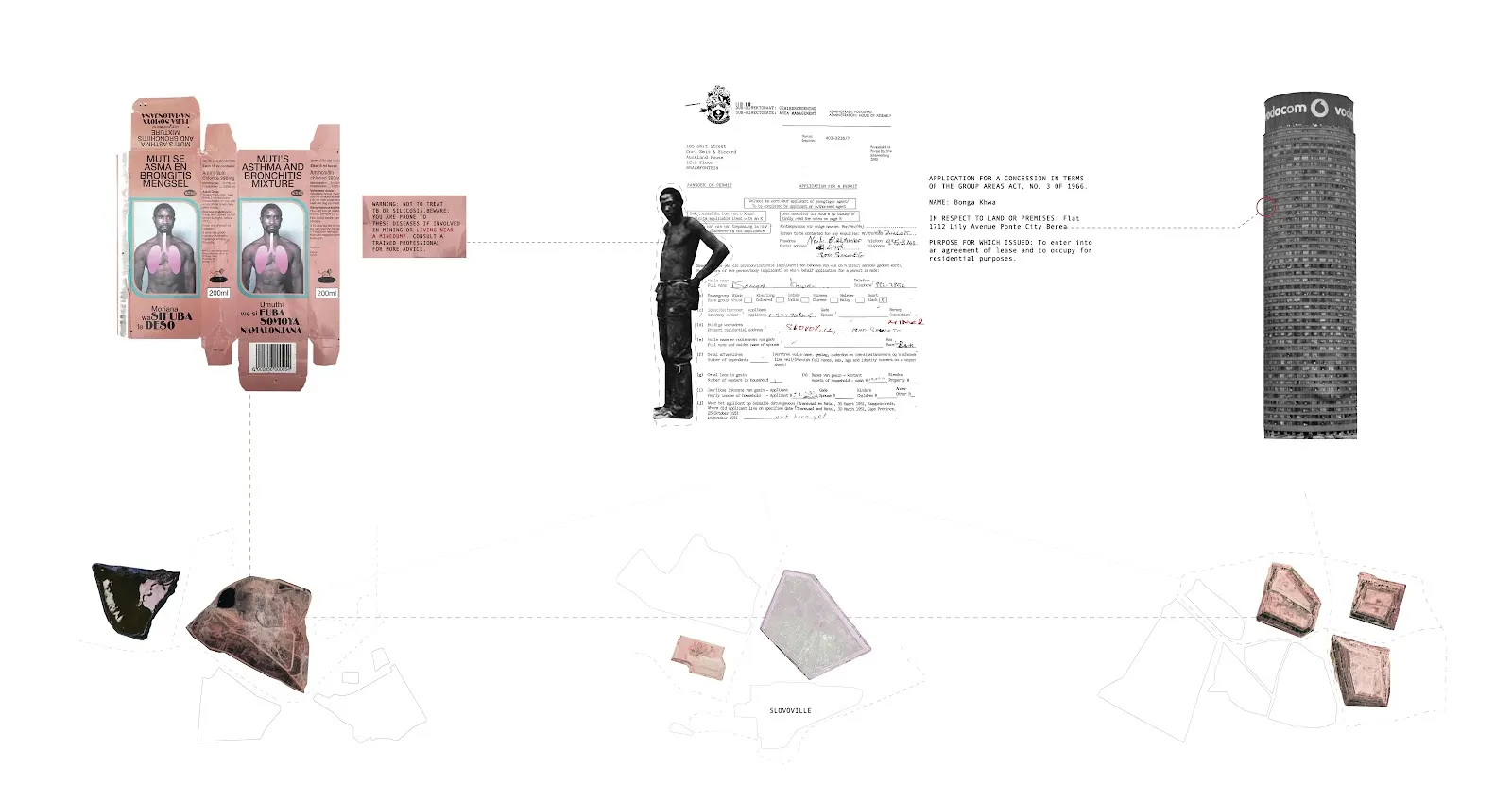

In a speculative drawing by South African architecture student Tarika Pather, she imagines a fictional Ponte resident, Bonga Khwa, as an informal miner in the abandoned mine dumps of Soweto. The fictional Bonga is shown with his imaginary residential permit to legally live in Ponte during apartheid—a set of dehumanising bureaucratic documents that starkly contrast evidence of the physical toll Bonga’s occupation has taken on his body. His thin skeletal frame parallels that of the young man pictured on the flattened box of medicine that was found amongst Ponte’s abandoned possessions between 2008 to 2014. The box advertises umuthi—an isiZulu word denoting herbal medicine—a common remedy offered to those with asthma. Mine dumps left abandoned and ill-maintained leave behind tailings that become dust blown and inhaled by miners and nearby residents who develop serious respiratory illnesses such as chronic coughing, sinus infection, asthma and tuberculosis. Despite threats to their health, the zama zama still mine these dumping sites for gold. In isiZulu, zama zama means “to try, attempt, or strive” and refers to a predominantly poor Black male workforce from rural provinces of South Africa and neighbouring countries such as Lesotho, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. The consequences of resource extraction make Ponte’s rocky core bear the traumatic traces of this colonial industrial past.